Data: Prize Papers

One of the best early-modern maritime sources is the Prize Paper Archive, an archive held at the National Archives in Kew (London). In a project that started at the University of Oxford in 2011 and later moved to Birmingham, we’ve collected data from this amazing archive to get an insight in maritime migration in the 18th century. But what are the Prize Papers, and how can we use this source to reconstruct early-modern migration patterns?

Lawful loot

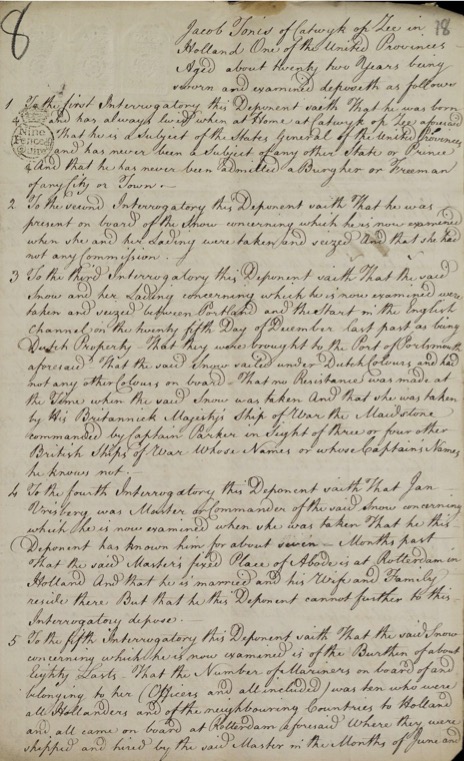

When a Royal Navy vessel or a private man-of-war captured an enemy ship, a court needed to establish whether the vessel was in fact a lawful prize: in other words whether the ship, crew or cargo belonged to an enemy state. To determine this they collected all documents aboard a ship, as they could serve as evidence. But they also cross-examined crew members (if necessary with the help of a sworn-in interpreter) about all matters relating to the ownership of the ship and its cargo. Commonly, three crew members were questioned, usually a cross section of the ranks aboard. Furthermore, because it involved a court case, supporting material, such as the ship’s papers and other administration is also present in the same file as the corresponding interrogation (see above for a collection of documents belonging to one ship).

The captured ships and sailors

From these interrogations (the picture below shows an example), we have created a relational database, containing all the information required by the interrogation rubric and therefore consistently present in the interrogations. The database comprises two tables, one of which deals with information about the ship, such as geographical markers of its ports of origin and destination, its tonnage, the number of nationalities aboard and information about its owner. This is linked to information about the crew, since there was normally more than one crew member interrogated per vessel. The crew table includes demographic information about the individual interrogated (including place of birth, residence and location of the employer, which allows one to determine if the person in question was a migrant or not), an indicator of his literacy, his rank and the length and nature of his relationship with the master of the vessel.

Insights from the crew interrogations

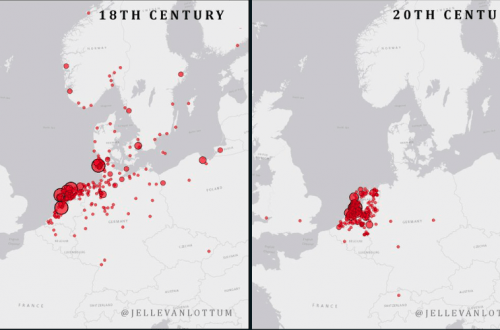

The interrogations exist from the end of the seventeenth up until the beginning of the nineteenth century, and are clustered around the various wars during this time frame, but such conflicts were regularly spread across the period, meaning that we can analyse change over time by looking at similar variables and comparable numbers of vessels in three clusters of years. The first cluster runs from c. 1702 to 1712, the second between 1776 an 1783, and the last between 1793 and 1803. As a consequence of this, our data on migration and mobility in the early-modern period ideally captures the growth in international trade and the increased integration of European labour markets during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

We hope to publish to dataset in 2019, but in the meantime will show some visualisations based on it! Watch this space, or follow Jelle’s twitter feed!